The Locked-In Effect: Or, Sorry Elon, But We Aren’t Likely to See a Widespread Crash in Home Prices

Updated Sun, Aug 13, 2023 - 7 min read

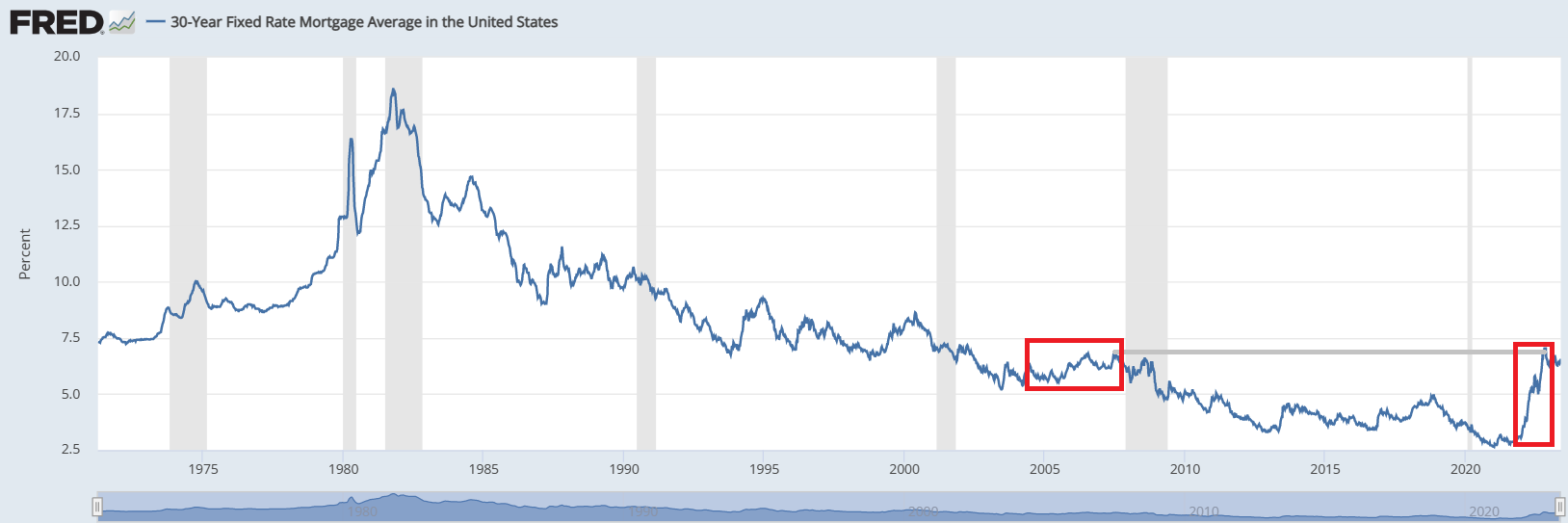

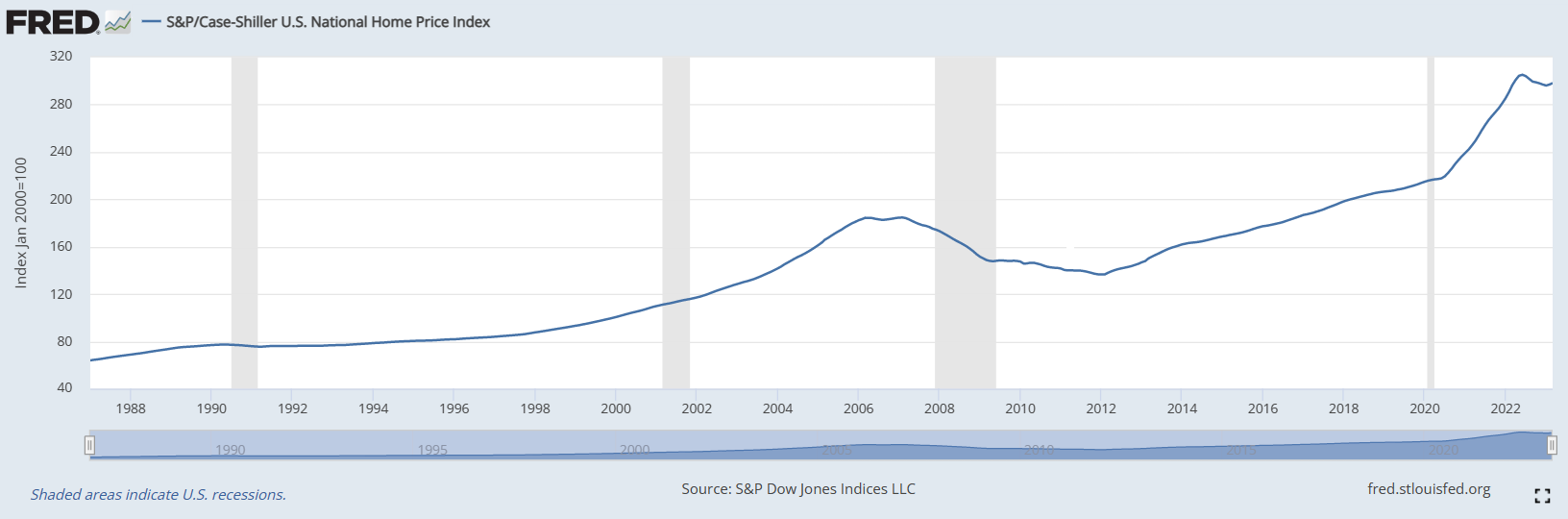

The drastic rise in interest rates has produced a rare phenomenon the GSEs have named the locked-in effect. While mortgage rates are reaching heights we have not seen in over a decade, what is truly unique about this interest rate environment is not how high the rate has climbed but how steep that climb has been. When we have seen interest rates like this in the past, we did not have a whole host of mortgages recently originated at less than half the new rate. This dramatic acceleration in interest rates has created the most unusual real estate market we have seen since 2008. Consider the following graph:

The grey horizontal line connects the last time interest rates were this high to the rate hikes we have seen over the last twelve months. (The regions shaded vertically with grey, on the other hand, represent periods of recession. The last two times we saw spikes like this in the early ’80s, they either occurred alongside or immediately before an economic downturn. Even then these spikes, which are similar in absolute magnitude, represent a smaller increase when you compare them to the starting interest rate.)

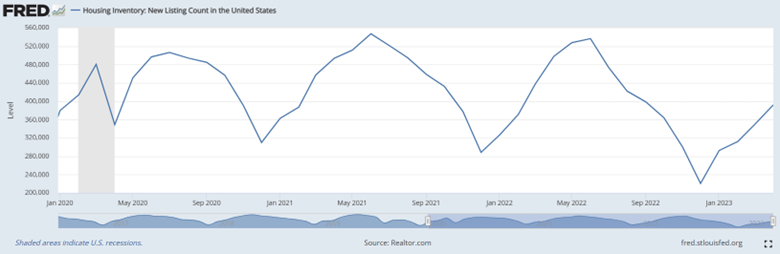

The red boxes show the path interest rates took to reach this level. You can see that the slope of interest rate increases was far steeper in the leadup to the present high. This is the cause of the locked-in effect. Anyone who got a loan in the last two years has a much better interest rate on his existing loan than he would on a new loan, and because early mortgage payments cover mostly interest, and very little principal, they have not yet built up much equity. Buying a different home would force these homeowners to acquire a new mortgage on much less favorable terms: locking them into their present home, which significantly reduces the number of homes becoming available for sale. The following graph shows the number of new MLS listings coming onto the market since the start of the pandemic. There is a clear downward trend.

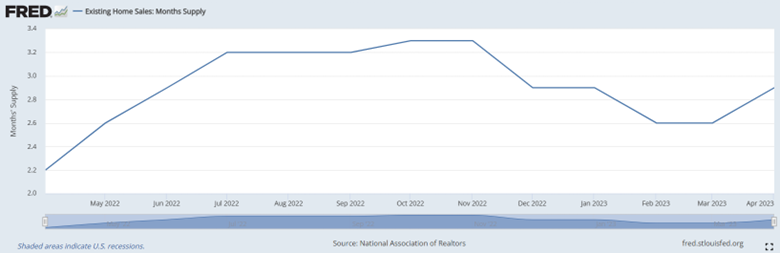

The locked-in effect is more pronounced in markets where housing makes up a larger percentage of household budgets. The above graph understates the extent of the locked-in effect; it is a more significant effect precisely in locales that are the least affordable, which are often those that have seen the most appreciation. Many markets have seen over 80% declines in sales volume, while only seeing much smaller increases in their months of inventory numbers (active listings/sales per month). This suggests that the supply constraint is canceling out much of the reduction in demand. Acknowledging that there is considerable regional variation in this metric, the following graph shows just how stable the months of inventory measure has been.

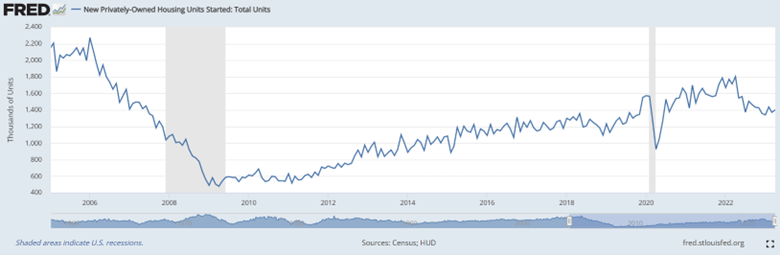

It is undeniable that high-interest rates reduce buyers’ ability to pay, which in turn reduces demand. This has produced a moderate decline in home prices, but this would have been far more substantial if the locked-in effect were not simultaneously reducing the housing supply, as discussed above. It has also caused new homes to become a larger percentage of total home sales than they have in the past (though existing homes still make up the majority of sales), both because new home construction recently increased during the pandemic housing boom and because existing home sales have declined. Home builders are not locked into the homes they are building by mortgages since they don’t have mortgages, and some can even offer favorable financing terms and other sales concessions. We can expect to see newly built homes constituting a higher percentage of transactions than they typically have.

This graph shows how the construction of new homes has increased, increasing some of the downward pressure on home prices that has accompanied higher interest rates. Notice the upward slope after a brief dip at the start of the pandemic, a slope that appears to be leveling out. While new construction is contributing to price declines, the fact that new construction activity continues at elevated levels suggests that home builders do not anticipate a significant correction in home prices, at least not in the markets in which they are building.

Let's connect, and see how we can help you stay ahead of the market.

Contact us

As stated above, while housing starts are down slightly, the change is nothing like the one we saw going into the 2008 financial crisis; further evidence that those who are talking about a widespread real estate crash are ill-informed:

Elon Musk recently predicted a crash in residential real estate. However, his analysis is based on the idea that the decline of commercial real estate guarantees a decline in residential real estate: This, however, is not the case; these are distinct markets and, while they do affect each other, their relationship is nowhere nearly that direct. First, the work-from-home revolution, which is reducing demand to rent commercial property, obviously does not reduce the need for housing: You still need a home if you are working from home.

Now, this could lead to localized price reductions in very expensive markets as workers move farther out, but this should not lead to a widespread collapse in real estate prices. Furthermore, working from home reduces demand for commercial property because it gives companies a reasonable alternative to paying high rents, but if companies manage to negotiate their rent down, many workers will still have to come into the office. The negotiating power work from home gives companies has an effect on rental demand of its own, but many companies will nevertheless continue to insist on working in person. Local price declines are possible, even likely, but a full collapse is not. Furthermore, Musk’s thinking ignores the locked-in effect; the locked-in effect is largest precisely where real estate prices represent the highest percentage of household budgets, namely expensive metro areas. Those who are very budget constrained are, of course, not able to buy, but they are also not able to sell in the present market either. Moreover, the number of cash buyers has increased, suggesting that there are people who sincerely believe the price declines we are seeing are temporary. We also see record amounts of single-family housing inventory being bought up by commercial interests of various sorts, something that would not be the case if the market anticipated a widespread downturn.

As you can see, the nationwide home price trend is leveling out, not crashing, though there is considerable variation from market to market. It is nothing like the nationwide loss of value we saw in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. Some who disagree with this might point to the decrease in the NAR’s median home price numbers, but this likely represents a tendency of newly formed households to buy more affordable homes than a real loss of value.

Finally, it is important to understand that home prices remain above their pre-pandemic levels—and that most homes were purchased before the pandemic. This means that loan-to-value ratios are still generally quite healthy: So, we are very unlikely to see the myriad of defaults (and REO contagion effects) that exacerbated the 2008 crash.

In summary, the locked-in effect is mitigating the slump in real estate demand, cushioning price declines significantly. While new home construction is also contributing to the decline, the fact that building activity has continued suggests that significant price reductions should be highly localized. We can expect local softening, but a crash is not going to happen.