The Weighting of Comparables: The Gap in USPAP

Updated Mon, Aug 21, 2023 - 5 min read

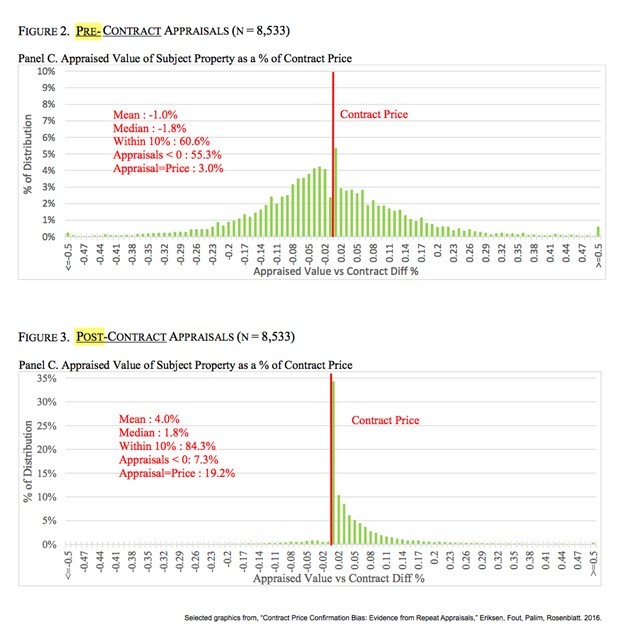

In a previous article, I discussed how appraisers are biased by their knowledge of the contract price. I cited a 2016 paper[i] by my colleagues at Fannie Mae which demonstrates just how serious this bias is. To refresh everyone’s memory, here are two graphs from that paper, one showing the distribution of appraised values on pre-contract appraisals and the other showing the distribution for post-contract ones:

As you can see, knowledge of the contract price affects an appraiser’s opinion of value. How is it that appraisers can meet or exceed the contract price at will? What is it about appraising that allows this much flexibility? If appraisers are choosing verifiably good comparables and making standard adjustments, it seems the process itself ought to produce values centered on the true value, not systematically above it. In short, why is appraising this gameable? We know these values are biased upward: It simply cannot be that every buyer is getting a deal, and every seller is getting “ripped off.” Most buyers are also sellers, after all. More to the point, if everyone is getting a deal, no one is getting a deal: That simply becomes the market price. Not everyone can be taller than average.

The standard tricks of choosing superior comps, under/over adjustment, and ignoring good comps that would pull down your subject’s value are well known; appraisal reviewers are constantly on the lookout for them. However, there is one last trick with which appraisers inflate values, the unequal weighting of comparables during reconciliation, the last step in the appraisal process. Reviewers are far less wary of this trick.

When appraisers come to a final opinion of value using the comparable sales method, they should take a weighted average of the adjusted values of their chosen comparables, ostensibly providing the most weight to the comparable that is most similar to the subject. Appraisers are free to weigh their comparables however they choose, and there is no requirement whatsoever to record what weights were applied.

A follow-up 2018 paper[ii] looked at appraisals from 2013-2017 and found that appraised values came below the contract price much more often if you take a simple average of the adjusted comp values. If one recalculates the appraised value by taking a simple average of the adjusted comparable values, 32% of appraisals fall below the contract price—as opposed to the 9% we generally see.

To improve appraisal quality, standards for the weighting of comparables must be established. At the very least, the URAR[iii] should require the appraiser to state what weights he used. This will force the appraiser to announce which comps he is giving the most weight to, making it easier for reviewers to notice inflated values. However, it should be possible to do more than this: USPAP should consider mandating proportional weighting of comparables based on their gross adjustments. At the very least, the appraiser can be required to state his weightings which can easily be checked upon appraisal submission for consistency with the appraised value. We just have the computer calculate the average using those weights. Even if no specific guidance around weightings is given, we can check that the rank order of gross adjustments and the provided ratings are consistent: Namely, that the least adjusted comp got the most weight, the second least adjusted the second most weight, and so on.

Let's connect, and see how we can help you stay ahead of the market.

Contact us

It could be argued that this might encourage under-adjustment, exacerbating the issue. This indeed will happen if no actions are taken to prevent under-adjustment, but as misadjustment is itself a serious problem, I would suggest USPAP provide more guidance around adjustments as well. For starters, FHFA, upon the recommendation of the TAF (The Appraisal Foundation), could insist the GSEs publish a table of standard adjustments for each county based on observed appraisal practice. Indeed, they could go further than this and ask that Collateral Underwriter’s adjustment factors be made public. This guidance would make it harder to get away with under-adjusting comparables. Third-party tools like our KAVM[iv] could also guard against this risk, using adjustment factors that are econometrically derived to flag unreasonably small adjustments. It is easier to guard against bad adjustments than bad reconciliation. After all, an appraiser is required to document his adjustments in far more detail than the final weighting of comps.

The Appraisal Foundation needs to familiarize itself with the literature regarding appraisal malpractice and to start thinking about altering USPAP to make appraisal review easier. In particular, they need to provide more guidance around the weighting of comparables. The first step, of course, is to make appraisers tell us what weights they used.

[i] “Contract Price Confirmation Bias: Evidence from Repeat Appraisals,” Eriksen, Fout, Palim, Rosenblatt, 2016.

[ii] Eriksen, Michael D. and Fout, Hamilton B. and Palim, Mark, and Rosenblatt, Eric, The Influence of Contract Prices and Relationships on Collateral Valuation (July 19, 2018). University of Cincinnati Lindner College of Business Research Paper, Available at SSRN

[iii] URAR stands for Uniform Residential Appraisal Report, the data standard that is replacing the older 1004, 1073, etc. appraisal forms.

[iv] Our Kukun AVM; AVM stands for automated valuation model and is a general term for any computer program that looks at a home’s features and produces an estimate of that home’s sale price.